Predator-Prey#

Author:

Date:

Time spent on this assignment:

Remember to execute this cell to load numpy and pylab.

0. Background#

In this assignment we are going to consider the evolution of predators and preys within an ecosystem.

We will focus on a single population of prey \(F\) (foxes) and a single population of predators \(B\) (bunnies).

Three possible things can happen:

Prey reproduce. Each prey produces \(\alpha \Delta t\) new prey in the unit of time \(\Delta t\). Therefore, the total number of new prey generated at time \(t\) depends linearly on how many prey \(B(t)\) there is with \(\Delta B(t) = \alpha B(t) \Delta t\). We can write this as a differential equation

\(\frac{dB(t)}{dt} = \alpha B(t)\)

Predators die. Like reproduction, the total number of predators that die at time \(t\) depends linearly on the total number of predators \(F(t)\) such that the change \(\Delta F(t) = -\gamma F(t) \Delta t\). We can write this as a differential equation

\(\frac{dF(t)}{dt} \propto -\gamma F(t)\)

Predators eat prey.

The rate at which predators and prey run into each other is going to depend multiplicatively as \(F(t)B(t)\). One way to think about this is if I scatter predators and prey randomly over a grid, the probability that they will be at the same place goes as \(\propto F(t)B(t)\).

If a prey gets eaten, then it’s gone so the change in prey is \(\Delta B(t) = -\beta F(t)B(t)\).

If a predator eats a prey then it is no longer hungry and can reproduce and so \(\Delta F(t) = \delta F(t) B(t)\).

We can write these as the differential equations\(\frac{dB(t)}{dt} = -\beta F(t)B(t)\)

\(\frac{dF(t)}{dt} = \delta F(t)B(t)\)

Combining 1-3 gives us two coupled equations:

These are called the Lotka-Volterra equations

Exercise 1: Solving the predatory-prey differential equations#

List of collaborators:

References you used in developing your code:

a. Modifying your code to run predator-prey equations#

In this exercise we will solve the differential equations which correspond to the predator-prey equations. 🦉Modify your dynamics code to solve these differential equations. I found it less confusing to just switch it so it works directly with \(B\) and \(F\). You can just use Euler integration (i.e, the first order-methods).

Note: Notice that before we dealt with a second order equation, but this is only first order.

### ANSWER ME

b. Building Plots#

Let’s set \(\alpha=1.0\), \(\beta=0.005\), \(\gamma=0.6\) and \(\delta=0.003\). Use a timestep \(dt=0.001\)

We are going to start with \(400\) prey (bunnies) and \(200\) predators (foxes).

Set up your code to run for time \(T=50\)

🦉Plot two graphs

Population vs time

prey (Bunnies) vs time.

predator (Foxes) vs time.

predator vs prey (a phase space plot)

### ANSWER ME

The dynamics for the parameters above (predator vs prey) result in what is called a limit cycle. This means that if I start with a given number of predators and prey, the total number cycles in this periodic pattern forever. You can see this either by seeing periodicity in the prey vs. time plots, or by noting that the phase space plot has a repeating orbit. Make sure to answer all these questions in full sentences with your reasoning.

Q: For the parameters above, is the first derivative of bunnies or foxes positive (which initially increases)?

A:

Q: Suppose you were to reverse the initial conditions, so that there are more predators than prey at the beginning. How would the answer to the above change (you can try it!)?

A:

Q: What is the relationship between the maximum in bunnies vs foxes? In phase, out of phase by 180 degrees, something else?

A:

c. Predator Phase Space Plots#

🦉Generate the phase space plots for a \(x\) prey and \(x/2\) predators for \(x \in \{50,100,200,400,600,800,1000,1200,1600\}\). (Use the same parameters as above). Also generate a plot of the minimum prey seen during an ecosystem simulation for a given number of starting prey.

### ANSWER ME

Q: What is the minimum amount of bunnies you ever see in your simulation?

A:

Q: As you increase \(x\), you will find that the populations start to crash near zero. Which population does that first?

A:

Q: Which value of \(x\), do you think is most likely to avoid extinction given these parameters ?

A:

d. Stationary points#

An interesting question we can ask: is there is some number of prey and predators we can start with so that the total number of prey and predators never change? This would be called a fixed point or stationary point.

We will determine the stationary point numerically. 🦉 To accomplish this, let’s write a function getDeviation(initial_population) which takes the initial population as a list [preyPopulation,predatorPopulation] and returns the standard deviation of the number of prey (np.std(listOfPreyVsTime)). If the total number of prey never change then its standard deviation is zero, and otherwise the standard deviation is greater than zero. Therefore, if we minimize the standard deviation then we will find the stationary point.

Now, all we have to do is call getDeviation a bunch of times with different parameters and figure out when it returns zero. There are lots of rich and interesting approaches to optimization problems like this, but we don’t have time to explore them. Here we are going to use a package from python calling out=scipy.optimize.minimize(getDeviation,x0). When it’s finished running, if you print out.x you can see which parameters it found.

Change \(\delta\) from 0.003 to 0.001 here

🦉Run the optimization and report the number of predator and prey you find.

Then make a plot of

prey vs. time and predator vs. time for these initial conditions

a phase plot of predator vs prey using these initial conditions .

You also might find it useful to turn off matplotlib’s formatting as follows: matplotlib.rc('axes.formatter', useoffset=False) so you can see more clearly what numbers are changing.

### ANSWER ME

### ANSWER ME

Q: Qualitatively what do phase plots look like when a stationary point is found?

A:

Exercise 2: Stochasticity in Predator-Prey equations#

List of collaborators:

References you used in developing your code:

Problems with simulating the ecosystem using the Lotka-Volterra equations:

There are two qualitative problems with simulating ecosystems using the Lotka-Volterra equations:

(1) In our simulations so far, we have found either stationary points or limit cycles. Both of these are unrealistic. Ecosystems are more dynamic than this. It’s not the case that once you have a certain population of predator/prey it returns to this number over and over again forever. This occurs because we are simulating the ecosystem deterministically - there is no randomness involved. Deterministic equations essentially can only do a few things: they can converge to fixed points, limit cycles or be chaotic.

(2) millibunnies: You may have noticed in your simulations that you ocassionally saw that your ecosystem had 1/1000 of a bunny and that this 1/1000 of a bunny recovered into a respectable population of 8000 bunnies. This is unrealistic, since there aren’t actually frational animals (and also it prevents extinction events). To go beyond this we need to recognize the discrete integer-ness of animals, which will require us to also include stochasticity.

a. The first bunny#

Let’s think about what \(dB = \alpha B(t) dt\) means. Previously we thought that it meant that in a unit of time \(\Delta t\) we got \(\alpha B(t) \Delta t\) new bunnies. But if \(\alpha B(t)\) is 0.2 and \(\Delta t=0.1\) we don’t get 0.02 bunnies. Instead we can think of it as the probability density of getting one whole new bunny as \(20\%\) and so the probability of getting a new bunny in a small interval \(\Delta t\) is \(0.2 \Delta t\).

We now ask the following question: What is the probability of getting your first bunny after time \(T+\Delta t\)? Well, we’ve taken \(T/\Delta t + 1\) steps. You have to not have gotten a bunny the first \(T/\Delta t\) steps. That probability is \((1-0.2 \Delta t)^{T/\Delta t}\). The probability of getting a bunny at step \(T/\Delta t+1\) is \(0.2 \Delta t\). So the total probability density is \((1-0.2 \Delta t)^{(T/\Delta t)} \times 0.2\)

Suppose we take the limit where \(\Delta t \rightarrow 0\) The the probability we get a bunny in an interval \(\Delta t\) is

This follows because

This is called a Poisson process, and it shows up in many situations, from nuclear decay to phone call frequency. It is essentially saying that a bunny reproduces on average every \(1/\alpha\) time, and once it has reproduced, it starts again with no memory of when it last reproduced. You can imagine that such a process might not apply to human behavior but we will use it for bunnies.

Let’s test this.

We can write a function TimeOfFirstBunny(alpha,deltaT) which takes the

rate \(\alpha\) (which is 0.2 in the above example) and

time-step \(\Delta t\)

and then returns the

first time we get one whole bunny.

This function should just loop over steps \(dt\) and return the time \(t\) if a random number is less then \(\alpha \Delta t\).

🦉Run this function 10,000 times with \(\alpha=1\) and \(dt=0.001\) and plot it with plt.hist(ts,100,density=1) (100 sets the number of bins and density=1 makes sure it is a normalized histogram).

On the same plot, plot

from \(T\in[0,35]\) to compare them. (Recall that if you have a numpy array you can do math operations on them using functions like np.exp)

### ANSWER ME

b. A faster algorithm to find the first bunny.#

Waiting to determine the time of first of bunny using the method of a. above is pretty slow. There is another algorithm that’s much faster (in the limit of \(\Delta t\rightarrow 0\)). The time to first bunny is

where \(r\) is a uniform random number between 0 and 1. The idea here is that we are drawing a sample from the Poisson distribution. This method is sometimes called “continuous time” because \(t\) can be any real number, and is not decided by a discrete time step.

Instead of analytically verifying this, let’s check this numerically.

🦉Write a function TimeOfFirstBunny2(alpha,deltaT) which returns \(-\log(r)/\alpha\) and make a plot comparing it to \(\alpha \exp[-\alpha T]\).

### ANSWER ME

c. Continuous time markov chain#

We will now use this to build a stochastic algorithm for predator-prey. Let’s translate everything we did above into this new continuous time language:

Prey reproduce at rate \(\alpha B(t)\)

\(\frac{dB(t)}{dt} = \alpha B(t)\)

At time \(t_1=-\log(r)/(\alpha B(t))\), the prey \(B \rightarrow B+1\)

Predators die at rate \(\gamma F(t)\)

\(\frac{dF(t)}{dt} \propto -\gamma F(t)\)

At time \(t_2=-\log(r)/(\gamma F(t))\), the predator \(F \rightarrow F-1\)

Predators eat prey at rate \(\beta F(t)B(t)\) which cause predators to reproduce at \(D F(t)B(t)\)

\(\frac{dB(t)}{dt} = -\beta F(t)B(t)\)

\(\frac{dF(t)}{dt} = \delta F(t)B(t)\)

At time \(t_{3a}=-\log(r)/(\beta F(t)B(t))\) the prey \(B \rightarrow B-1\)

At time \(t_{3b}=-\log(r)/(\delta F(t)B(t))\) the predator \(F \rightarrow F+1\).

This latter point is a bit weird but works. Both the fox eating the bunny, and the reproduction of new foxes is proportional to how much the fox eats, so these two processes in practice can be separated in this way.

Now for our algorithm:

Compute times \(t_1, t_2, t_{3a}, t_{3b}\).

use a different random number \(r\) for each \(t_i\), don’t share the same \(r\)

One of these times \(t_i\) happens first.

Perform event\(_i\) (add a prey, or remove a predator, etc.) Update \(t \rightarrow t+t_i\).

Forget about all the other times (the rates have changed..you have more prey or something).

It feels funny that this is legit, but it is. (This comes from the fact that poisson processes are memoryless).

check that we don’t have 0 Prey or Predators. If we do, stop the simulation.

Do it over again.

Write a function RunEcosystem which inputs:

total time \(T\)

Initial conditions \(B_0\) and \(F_0\)

and make sure to keep track of \(\alpha,\beta,\gamma,D\).

Then have RunEcosystem apply this stochastic algorithm for time \(T\) and return

a list

tsof times \(t\)a list

Bsof prey \(B\) at those times.a list of

Fsof prey \(F\) at those times.

Notice now that your times will not equally spaced!

### ANSWER ME

d. Stochastic Populations#

🦉Plot

Population vs t

prey vs t

predators vs t

Phase plot (predator vs prey)

for \(T=50\), \(B(t=0)=100\), \(F(t=0)=50\), and \(\alpha\)=1.0, \(\beta\)=0.005, \(\gamma=0.6\), and \(\delta=0.003\)

On the same plots, show the results for the deterministic algorithms. Run it a few times to see the effect of stochasticity.

### ANSWER ME

e. Stationary again#

🦉Do the same thing as d. for the parameters you found above which give you a stationary point. Don’t forget to change \(\delta=0.001\) For this, go out to \(T=1000\)

### ANSWER ME

Q: Do the number of bunnies change as a function of time?

A:

Q: Qualitatively what is the effect of running the stochastic simulation at the stationary point?

A:

e. Extinction#

In this part we are going to determine the amount of time until one of the two species goes extinct given the initial number of prey/predators. Let’s call this an extinction event.

Use parameters

\(\alpha=1.0\)

\(\beta=0.008\)

\(\gamma=0.3\)

\(\delta=0.002\)

and assume we start with the same number of predators and prey.

🦉For \(B_0\in\) preyNum w/ preyNum=np.arange(20,600,1), run your ecosystem until there is one extinction event. Record the time \(t\) this event happened and graph \(t\) vs. initial prey number.

np.arange(20,60,1) first.

### ANSWER ME

f. Window Averaging (cleaning data)#

This data is going to look noisy. 🦉To make it look nicer do a running mean of your data with a window-size of 20 and plot it. This will be smoother.

What value is your largest time to extinction (post window-averaging)? I find my results are around 160-190

### ANSWER ME

Q: I would have expected that this curve would be more monotonic. The more prey you had, the less likely anyone would go extinct. Is this correct? Do a calculation with B0=600 and describe why the bunnies go extinct quickly.

A:

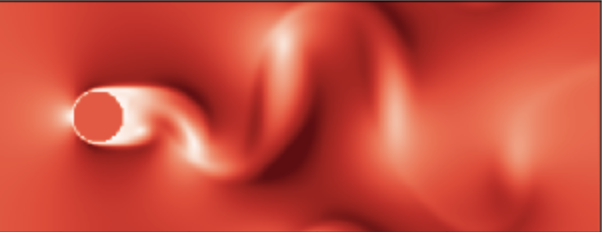

Exercise 3: Agent Based Predator-Prey Simulation#

This is Extra Credit!

List of collaborators:

References you used in developing your code:

In this exercise, we want to simulate an agent-based model of the predator-prey simulation. Instead of the previous exercises where you are using a differential equation, here we are going to simulate each individual bunny and fox separately as an agent. These bunnies and foxes are going to live on a \(s \times s\) grid. Foxes will keep track of how full they are. All foxes are born with a fullness amount \(F\). The dynamics of our simulation will be:

The bunnies and foxes will be allowed to move around the grid. At each time step, every bunny and every fox will decide either to stay where they are or try to move in one of four directions. If they decide to try to move, they will move if its empty of the same type of animal (i.e. foxes don’t move to where foxes are). If someone is in the direction they wanted to go, they will stay where they are.

Every time step, the fox gets \(f\) less full.

When the foxes and bunnies are on the same grid point (after everyone moves) one fox on that grid (pick arbitrarily) eats all the bunnies on that grid. The foxes full-ness increases by the number of bunnies they eat.

An \(\alpha\) fraction of bunnies reproduce (appearing at the same location) at each time-step.

All foxes whose full \(F\) is more then \(R\), reproduce (at the same location) at each time-step.

All foxes whose full \(F\) is less then 0 starve.

To do this, we are going to have a class to store each “fox” or “bunny”:

@dataclass

class fox:

location: list = field(default_factory=list)

full: int = 2

and

@dataclass

class bunny:

location: list = field(default_factory=list)

eaten: bool = False

The fox starts full with an amount 2 and the bunny starts not eaten. There is no default location for them.

To set up a fox you can do myFox=fox() and to access the location of the fox you can do myFox.location. If you want to push your fox back onto a list you can do myList.append(fox()).

To implement this project, you will use four data structures:

a list of foxes

a list of bunnies

a \(s\times s\) numpy array foxLocations that shows how many foxes are in each grid

a \(s\times s\) numpy array bunnyLocations that shows how many bunnies are in each grid.

To set things up, first set up the grid with a density of 10% bunnies and 1% foxes.

foxLocations=np.random.choice(2, size*size, p=[.99,0.01]).reshape(size,size)

bunnyLocations=np.random.choice(2, size*size, p=[.9,0.1]).reshape(size,size)

Write code

def LocationsToList(locations):

which takes the bunnyLocations (foxLocations) and generate a list of bunnies (foxes) with correctly intialized fox.Location and bunny.Location parameters -i.e. suppose your grid has bunnies at locations (1,2) and (4,3). Then LocationToList(bunnyLocations) should return something like the bunnies list from

bunnies=[]

bunnies.append(bunny())

bunnies[-1].location=[1,2]

bunnies.append(bunny())

bunnies[-1].location=[4,3]

return bunnies

(obviously you have to make this work no matter what’s in bunnyLocations).

Also write a function

def GetLocations(animalList)

that does the opposite. It tkes the list of bunnies (foxes) and produces the location array of bunnies (foxes).

You can test that these work by call LocationsToList(GetLocations(LocationsToList(myLocations))) to get back the same thing you started with.

Your next step is to write a function

def Move(creature,creatureLocations)

which (say we are doing foxes)

loops over all the foxes

for each fox flips a nine-sided coin and decides whether to stay or go a particular direction

attempts to go that direction and does so if no fox is there (otherwise stays put)

Update the location in the fox class and updates the location array of the fox appropriately You should check when you leave the function that the locations are still correct.

You should be able to check that you move class works. One good test is to make a bunch of moves and verify that the total number of creatures stays fixed. Also check that np.sum(foxLocations) and len(foxes) is the same. Also check that np.max(foxLocations) is one and np.min(foxLocations) is zero.

After you’ve written the move function, now you can write the function

def Eat(bunnies,foxes,bunnyLocations,foxLocations):

If there are foxes and bunnies on the same cell, have the foxes eat all the bunnies making sure you update

the bunny locations (they’re gone)

the bunny eaten flag

the fox full state

Also remove any eaten bunnies by the end of the function.

Finally, implement two reproduce functions separately for foxes and bunnies. The fox function should do the following:

if the foxes full state is \(\leq 0\) then the fox starves

if the foxes full state is \(\geq 5\) then the fox reproduces.

The bunny function should do the following:

an \(\alpha\)’th fraction of the bunnies should reproduce.

Use

\(\alpha=0.01\)

\(R=5\)

\(s=80\)

\(f=0.1\)

Run your code and plot both

bunnies and foxes vs. time

a phase plot of foxes vs. bunnies

an animation (see the code below). To do the animation you need to keep snapshots of the fox-locations and bunny-locations at each step.

You should see features reminiscent of your previous work.

### ANSWER ME

### ANSWER ME

Acknowledgements:

Bryan Clark (original)

© Copyright 2020

–