Chaos#

Author:

Date:

Time spent on this assignment:

Note: You must answer things inside the answer tags as well as questions which have an A:.

In this project we are going to learn about pendulum and chaos. We will start with a single pendulum, examining phase space diagrams and animating trajectories, and moving toward a double pendulum. Then we’ll wrap up by using automatic differentiation to look at the same problem, recast in a different form, to write a more general solution to the double pendulum problem.

Exercise 1. Single Pendulum#

List of collaborators:

References you used in developing your code:

You will use the following animation code for exercise 1

Help with animateMe: There are two animate functions that accept positions (the angles, technically) and params. The positions argument needs to be passed as a nested list [positions] and the positions array needs to be 2-dimensional. You can check the shape of your array using positions.shape to ensure it is in the right format of (N,1), which is what the animation functions expect. If your positions array is 1D, you can reshape it using positions[:,np.newaxis].

a. A Single pendulum#

When working with pendula, instead of keeping track of the position \((x,y)\), we instead are going to keep track of the angle \(\theta\).

In this exercise, we are going to simulate a pendulum with a rigid rod \(L\) and a fixed mass \(m\) at the end of it. We can define the position of the pendulum by the angle it makes with respect to hanging down (at \(\theta=0\)).

You can force your code to use theta simply by giving initial conditions and velocities for a single dimension (i.e. params['initPos']=np.array([0.1]) would start you pendulum at 0.1 radians.

The “force” (angular acceleration) of a single pendulum is \(\alpha(\theta)= -g\sin(\theta)/L\). Modify the force function to use this new “force”.

🦉Run a simulation with no initial velocity and an initial angle of \(\theta=0.6\) and a \(dt=0.01\) for a time \(T=10\). Set \(L=1\) (params['l1']=1).

Plot

\(\theta\) vs. \(t\)

\(y\) vs. \(x\) (include the origin on this plot, and equalize the axes scale)

a phase space diagram (\(\omega\) vs \(\theta\))

and animate the pendulum.

A phase space diagram is a graph displaying the position and velocity of an object on the abscissa (x axis) and ordinate (y axis). Since an undamped, undriven harmonic oscillator moves with

its phase trajectory will be an ellipse with axes of lengths \(2A\) and \(2A\Omega\).

Q: Does the phase space diagram match your expectations? Explain

A:

b. Pendula and different starting positions#

Recall in your intro mechanics class (Physics 211/etc) that you know the analytic solution for a pendulum is $\( \theta(t) = \theta_0 \cos(\Omega t) \)$ However, that solution only works for small angles.

🦉Let’s quickly check this, by looking at the “error” (difference) against the ‘analytic solution’ for \(\theta_0 \in \{0.1,0.3,1\}\).

Then plot their phase space diagrams on top of one another. What do you see?

###ANSWER HERE

Q: Describe the “error” plot; what’s going on?

A:

Q: What does the phase space diagram look like now? Do any of these initial conditions change the “simple” behaivor of the pendulum?

A:

c. Damped and Driven and phase plots#

The behavior of a “simple” pendulum becomes less simple when you add damping and drive the system.

Suppose we make a pendulum from an object of mass \(m\) at the end of a rigid, massless rod of length \(L\). The rod is suspended from a bearing which exerts an angular velocity-dependent drag force on the pendulum. Because we are using a rod, not a string, the pendulum can swing in a full circle if it is moving sufficiently quickly. A motor attached to the pendulum provides a sinusoidally varying torque. Gravity acts on the pendulum in the usual way.

The equation of motion for the pendulum is then

The first term to the right of the equal sign is the torque due to gravity. The second term is the velocity-dependent damping, while the third term is the external driving torque. The symbols \(\beta\) and \(\gamma\) represent constants.

Do some algebra:

or

where \(A\) and \(B\) are positive constants. We can rewrite this as a pair of first order equations:

🦉Please write a program to calculate (and graph) \(\theta\) vs. \(t\) and \(\omega\) vs. \(t\) for the pendulum. You may find it convenient to write your expression for the force in this way:

def Force(t,pos,vel,params):

A = params['A']

B = params['B']

C = params['C']

OMEGA = params['OMEGA']

F = -A*vel - B*np.sin(pos) + C*np.sin(OMEGA * t)

return F

Make sure when you make your plots that all values of \(\theta\) are \(-\pi \leq \theta \leq \pi\). When you produce your graphs make sure that you wrap things so that those are the only values that you see on your graph.

Run your program with the following parameters and be sure to include all the plots in your Jupyter notebook.

Parameter |

Version 1 |

Version 2 |

Version 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

\(A\) (damping) |

0 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

\(B\) (restoring force) |

0.1 |

1 |

1 |

\(C\) (external driving force) |

0 |

0.1 |

2 |

\(m\) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

\(\Omega_\mathrm{ext}\) (driving frequency) |

N/A |

2 |

1.2 |

\(\theta_0\) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

\(\omega_0\) |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

\(t_{max}\) |

120 |

120 |

500 |

\(dt\) |

.01 |

.01 |

.01 |

Version 1 is an undamped, undriven pendulum. The amplitude of motion is small enough so that it behaves very much like a harmonic oscillator with oscillation frequency \(\Omega=\sqrt{0.1}\). Version 2 is lightly damped, and driven at twice its natural frequency. As the initial motion (which has \(\Omega=1\)) dies away, the driving force will cause it to oscillate at the same frequency as the driving frequency.

It takes longer for the pendulum to settle down than it did in case 2.

If we had tuned the parameters just right, we might have found a set for which the motion was chaotic, never settling into a periodic mode.

### ANSWER HERE

d. Simple pendulum phase space trajectory#

The phase trajectories of driven nonlinear oscillators can be much more complicated than this. 🦉Please generate phase space diagrams for the simple pendulum using the parameters for version 2 and version 4 (shown below again). Note that \(t_\textrm{max}=500\)

Parameter |

Version 2 |

Version 4 |

|---|---|---|

\(A\) (damping) |

0.1 |

0.1 |

\(B\) (restoring force) |

1 |

2 |

\(C\) (external driving force) |

0.1 |

2 |

\(m\) |

1 |

1 |

\(\Omega_\mathrm{ext}\) (driving frequency) |

2 |

1.2 |

\(\theta_0\) |

0 |

0 |

\(\omega_0\) |

0.1 |

0.1 |

\(t_{max}\) |

500 |

500 |

\(dt\) |

.01 |

.01 |

###ANSWER HERE

If you want, go ahead and animate these pendula

Exercise 2. Double Pendulum#

List of collaborators:

References you used in developing your code:

Single (rigid) Pendula are somewhat boring. We can compute most things about them analytically. A double pendulum on the other hand has a much richer behavior. In this exercise you are going to simulate a double pendulum.

a. Simulating double pendula#

Modify your code to simulate a double pendulum. Now instead of representing the location of your pendulum with one \(\theta\) you need to use two \(\theta\). (Be careful you are dealing with the mass correctly). Again, this can be mainly accomplished by playing with your initial conditions.

Now, you need to get the force to work. The force for a double pendulum is somewhat complicated. To compute the force you either need to:

derive the force carefully

This is a bit annoying because part of the force involves the tension in the rod (i.e. the first mass has a force of \((-T_1 \sin(\theta_1) +T_2 \sin(\theta_2), T_1 \cos \theta_1 - T_2 \cos \theta_2 - m_1 g) ) \) Because we don’t know what \(T\) is, we need to do some algebraic manipulation to be able to write \(\frac{d^2\theta}{dt^2}\) as a function of \(\omega=\frac{d\theta}{dt}\) and \(\theta\) (which is what we need)

use the Euler-Lagrange equations. This ia a better approach for systems with constraints and is something you will learn in classical mechanics.

At the moment we will just give you the effective force1:

f1=-l2/l1 *(m2/(m1+m2))*omega2**2*np.sin(t1-t2)-g/l1*np.sin(t1)

f2=l1/l2 * omega1**2 * np.sin(t1-t2)-g/l2*np.sin(t2)

alpha1=l2/l1*(m2/(m1+m2))*np.cos(t1-t2)

alpha2=l1/l2*np.cos(t1-t2)

den=(1-alpha1*alpha2)

omega1_dot = (f1-alpha1*f2)/den

omega2_dot = (-alpha2*f1+f2)/den

Note that omega1/omega2 here mean the velocity or \({d\theta_i}/{dt}\), \(i=1,2\) respectively. Also, in the notation above \(t1=\theta_1\) and \(t2=\theta_2\), not to be confused with the tensions!

Put this force in your code.

🦉Run with the following parameters:

params={ 'm1':1.0,

'm2':1.0,

'l1':1.0,

'l2':1.0,

'T' :15.0,

'g' :9.8,

'dt':0.01,

'initPos' : np.array([1,1+0.11]),

'initVel' : np.array([0.0,0.0])

}

and make a phase space plot of the system for both the first mass and the second mass (on the same plot). Also go ahead and animate it.

Then switch to use the initial position of 'initPos': np.array([3.14,3.14+0.11]),. How do these compare?

In the animation, you may not want to use all the points.

### ANSWER HERE

Q: Does the inner bob (\(m_1\)) act like a simple pendulum? Use the phase space diagram in your answer

A:

Q: How does the behavior of the pendulum change compared to a simple pendulum as the initial angle is increase?

A:

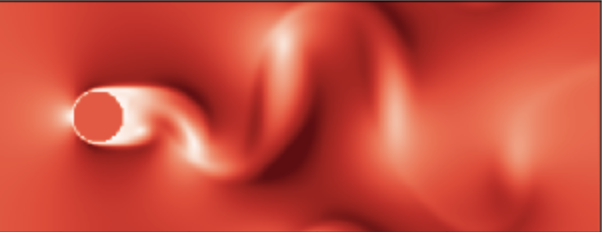

b. Chaos#

Our goal now is to see that this double pendulum is chaotic. Chaos means that if the system starts with very similar initial conditions, that the result will look very different in the future (long times). Go ahead and run a series of 10 initial conditions except that each one differs from the previous one by an initial angle on the second pendulum of \(10^{-4}\), i.e. params['initPos'][1]+i*1e-4,params['initPos'][1]+(i+1)*1e-4

Animate them all simultaneously to see what happens.

Hint: Your code should have something like this

params={ 'm1':1.0,

'm2':1.0,

'l1':1.0,

'l2':1.0,

'T' :15.0,

'g' :9.8,

'dt':0.01,

'initPos' : np.array([3.14,3.14+0.11]),

'initVel' : np.array([0.0,0.0])

}

for i in range(10):

pos = params['initPos']+np.array([0,i*1e-4])

vel = params['initVel']

run_simulations(pos,vel)

###ANSWER HERE

Acknowledgements:

Ex 1: George Gollin (original); Bryan Clark, Ryan Levy (modifications)

Ex 2: Bryan Clark (original)

© Copyright 2021