An Introduction to Modern Computational Physics#

Physics 246, Fall 2025

Thursday 4:00-5:50pm CST

Room: Loomis 158

2 credit hours

Course Texts: This one!

Welcome! Computation is powerful. In this course, you are going to learn how to use computation to do amazing simulations: compute how general relativity changes the orbit of Mercury; simulate turbulence; compute the effect of predator and preys on an ecosystem; run a quantum algorithm; and more! We’ve searched and distilled from the world some of the coolest physics we know for you to learn to simulate. Our primary goal in this class will be to help you make these simulations.

Course Logistics#

Lectures: Thursday 4:00-5:50, 276 Loomis

Professor: Bryan Clark

email:

Office Hours:

TA(s):

email:

Office Hours:

email:

Office Hours:

Online Tools#

Google Colab: On Google Colab you will be able to program your code in a jupyter notebook and submit it for us to grade. Please sign in to your Illinois account. While working on the assignment, you will share each of your colab assignments with the professor and the TA (but no one else). You can load things in google colab just by clicking on the relevant button in the notebook (looks like a shuttle). You must then save to your google drive and it will be there later when you go to google colab!

Gradescope: You will submit your projcts via Gradescope, which will also contain your grades and your returned assignments. You will have 2 seperate submissionts per assignment, that includes a printout of your Colab document in .pdf format and your original .ipynb. Both submissions are required for each project to obtain credit. Specific instructures with screenshots can be found on the slides from Lecture 1

Calendar#

(These are the dates that we work on the assignment in class; the assignments are due one week later)

Date |

Assignment |

|---|---|

Aug 28 |

N Ways to Measure PI Lecture 1 |

Sep 4 |

Dynamics Lecture 2 |

Sep 11 |

Orbital Dynamics Lecture 3 |

Sep 18 |

Exoplanets Lecture 4 |

Sep 25 |

Chaos Lecture 5 |

Oct 2 |

Particle Physics Lecture 6 |

Oct 9 |

Classifying Galaxies Lecture 7 |

Oct 16 |

Random Walks Lecture 8 |

Oct 23 |

Markov Chains Lecture 9 |

Oct 30 |

Predator-Prey Lecture 10 |

Nov 6 |

Climate Dynamics Lecture 11 |

Nov 13 |

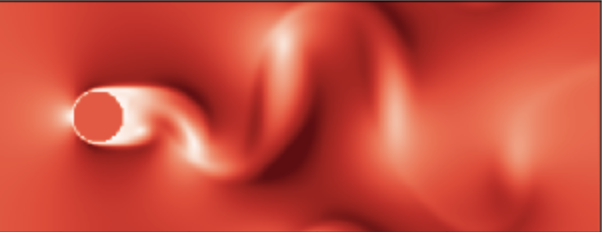

Fluid Dynamics (Jaki probably traveling) Lecture 12 |

Nov 20 |

Quantum Computing Lecture 13 |

Nov 27 |

No class! Fall Break |

Dec 4 |

Building a Physical Qbit Lecture 14 |

Coursework#

Computational Assignments#

The heart of this course will be a series of computational assignments.

You will work on the assignments both during class and as homework.

Homework will be graded on the follwing criteria:

60% Working code that solves the problem

10% Documented code (comments explaining your work)

10% Cleanliness of code (removed any faulty code - no side quests!)

10% Well-named variables (e.g. the mass of a star is called “Mass” not “paramter1”)

10% Readable plots - when applicable (axes labeled, reasonable color scheme, visible and distinguishable lines, reasonable range etc)

The assignments consist of 80% of your grade.

You must BOTH share your code (see below) AND turn in the PDF on time into Gradescope. If we only have one or not the other, we will not grade your assignment (and it will be counted late if the other part is turned in after the due date).

Each assignment is due at the beginning of the next class unless otherwise noted. Extension may possibly be granted under extreme situations, please email Surkhab and Max. We will then respond if the extension has been granted. The following information:

broadly why you need the extension (illness, family emergency, etc)

when you will be able to submit the assignment by (this is the new official due date if the extension is granted.)

Solutions to the homeworks will not be given.

Partial credit exists but will be limited.

You may collaborate on assignments but must submit your own work.

You may not use generative AI, LLM’s, etc. You must turn this off in google colab.

Good Coding Practices#

Codes generally have a lifetime beyond whatever they were originallized designed for. Maybe in your early days of physics you write a code to solve an integral pretaining to something in Newtonian mechanics. Then you get a bit older and you take Quantum Mechanics and you want to reuse that code so you change it a bit for the new problem. A year or two later you go onto grad school and once again reuse that code in a General Relativity class. Over time your code must adapt to all these changes and depending on how well you wrote your original code those changes may be a lot easier (or harder) to make. Imagine that you “hard coded” your unit scale in the original code to be in kilometers - that would be very challenging once you switched to Quantum Mechanics because you’d need to cary around a bunch of extra orders of magnitude! Changing your code would be even harder if you haven’t documented what you did in the original code, especially if all your parameters are named “paramater1, parameter2, etc”. Thus, we will be working on not just writing code in this class but on good coding practices. In this class we want to built good coding practices and habits from day one. Thus, this will also be a component of your grade.

Readable plots#

Plots should be labeled, visual appealing, readable Here’s a quick tutorial of what is a bad vs good plot (feel free to steal this code!).

For futher resources, see Data Visualization using Matplotlib (and the links within).

Instructions for submitting your assignments#

Once you are finished working on an assignment, first make sure that it is shared with the course staff by clicking “Share” in the upper right hand corner in the Colab window and adding us via email address. Then, at the bottom of that same “Share” menu, click “Copy Link” to get the sharing link to your Colab document. Next, save a .pdf printout copy of your Colab document. This can be done by the following code

from google.colab import drive

drive.mount('/content/drive')

!cp /content/drive/MyDrive/Colab\ Notebooks/Dynamics.ipynb ./

!jupyter nbconvert --to HTML "Dynamics.ipynb"

where you replace your filenames above with the appropriate ones for your assignment. Then open the HTML file in your web browser and print from there.

Assignments are submitted via Gradescope, which requires two simple steps. First, paste the aforementioned sharing link into the “… (Colab link)” section. Second, upload your printout .pdf file into the “… (PDF file)” section and then submit that assignment.

We will review both the printout and Colab code while grading your assignment, so please refrain from editing the Colab document after the submission deadline.

Final Project (20% of the grade)#

During the final period, you will put together a project that demonstrates something in computational physics. It can be an extension of some of the work that you did in class or something new. This project can be done in small groups (2-4 people). Projects have to be approved by course staff. For your project you will submit a jupyter notebook (in the spirit of what you’ve done in class but expository) as well as give a 5 minute presentation during the finals period for the course.

Extra Credit#

There will be occassional opportunities to get extra credit. To zeroth order these exist because I think they are cool and useful for understanding computational physics but I can’t justify within the 2 credit hours of the course.

Extra credit assignments will often be described poorly (maybe even something like, `get a full solar system simulation working’). If you have questions about it, please ask before you spend too much time on it. Also, we have no obligation to make extra credit typo-free. Please try to answer the question we mean to be asking.

For the extra credit, per exercise, the grading is all or nothing. We aren’t going to hunt for typos and give partial credit for sortof working code. The amount of extra credit per exercise/etc is listed on the assignment.

Coding and Research#

Grading#

Computational Assignments: 80%

Final Project: 20%

Your final numerical score is computed as 100 x (0.80 x (Homework Points + Extra Credit Ponts)/(Total Homework Points) + 0.20 x Final)

The final breakdown of how your grade depends on your numerical score goes as:

100+: A+

93-100: A

90-93: A-

88-90: B+

83-88: B

80-83: B-

78-80: C+

73-78: C

70-73: C-

60-70: D

<60: F

Scores are inclusive of the bottom number - i.e. a 90 gets an A not a B+. All problem sets count for the same amount. Unless otherwise noted, every exercise in a problem set counts an equal fraction of the assignment and every part (a,b,c,…) of an exercise counts as an equal fraction of the exercise. 5 points of the problem set will be for mandatory questions (e.g. time spent on assignment, references, collaborators).

Sometimes there are typos in the assignment (although we are working hard to remove them). Please ask when confused! Don’t spin your wheels a long time on something that might be a typo. These aren’t trick questions - we are trying to ask reasonable things.

Policies#

Attendance#

Students are strongly enoucarged to attend class, participate in lectures, and make use of office hours. While no explicit attendance requirements are in place, participation is factored in at the end of the semester if a student has a boarderline grade as well as for when students ask for homework extensions. Thus, it is in the student’s best interest to regularly attend class.

The first half of class includes a lecture/overview of the problem. The second half of class provides you with time to work on the problem (in small groups and with the instructuor and TAs available for help). The first half of class is invaluable to introduce the problem, the second half can help you get started.

If a major event occurs e.g. death in the family, major illness etc, it is best

About using code you find on the web#

The quickest way to deal with the arcana of programing is to ask Google for examples of what you are seeking to accomplish. But you will need to use your judgment in doing this: the Google search “how do I use color maps in python?” is fine, while “show me a script that calculates pi” is not. And you should always credit the original source of code that you paste into your own programs in a comment that includes the URL for the original code. If an author says that his/her code is not to be copied or incorporated into your programs, then DON’T.

The goal of this course is for you to deeply understand this material. For this to work, you’ll need to write your own code.

About Large Langauge Models#

In a similar vein, you aren’t allowed to use LLM for help. This includes chatGPT, google bard/gemini, claude, etc. You must turn off the generative AI in colab if you have it on (which it might be by default).

Academic Integrity#

You must never submit the work of someone else as your own. We understand that many of you will find it helpful to work with other students to master Physics 246. But when you collaborate with your study group on homework assignments, you must be a full, active participant in developing the solutions that you submit for credit.

It is cheating to receive answers from another student and then use them as your own. It is cheating to submit as your own work solutions that you find by searching on the worldwide web (though see “About using code you find on the web”) It is cheating—and a violation of U.S. copyright law—to give (or sell) course material to someone else who intends to redistribute and/or sell it.

All activities in this course are subject to the Academic Integrity rules as described in Article 1, Part 4, Academic Integrity, of the Student Code.

Useful Python#

Intro Python Jupyter Notebooks:

Why this course?#

As the needs of our students evolve—there is, for example, increasing focus on early readiness for research—the Physics faculty are obliged to adjust both what we teach, and how we teach.

There is a rich tradition of innovation in engineering pedagogy at Illinois. Fifty years ago UIUC became the first school to teach its undergraduates to design computers. More recently, our colleagues have become national leaders in successful efforts to improve instructional outcomes in elementary physics. We intend to continue this Illinois tradition by incorporating computational literacy into the set of core competencies to be mastered by our students.

Just as we require physics majors to enroll in courses taught by Mathematics, but teach the applications of mathematics to physics in our own courses, we hope to do the same with programming. We will continue to require that our students take an introductory course in Computer Science, while incorporating into our own courses machine-based approaches to problems that cannot be solved analytically. Examples include chaos and nonlinear phenomena; fluid dynamics; real-world electrodynamics; quantum mechanics of multi-electron atoms.

This course is a first step. From it, we expect that students will come away with a better grasp of complex phenomena and will be prepared to engage with research experiences that would otherwise have been inaccessible. This will bring to the department’s scientific efforts the collateral benefit of an enlarged pool of competent research assistants. If we are successful, our methods should generalize to other disciplines in science and engineering.

Background: The technical foundation for physics majors includes material in physics, mathematics, computer science, and chemistry. But though the courses taught outside the Physics Department provide an excellent introduction to important subjects, they are insufficiently dense in application to specific physics topics to stand on their own. We find this to be especially true in mathematics and computer science. Consequently, the Physics Department offers undergraduate and graduate courses on mathematical methods for physics, as well as a graduate course in computation.

Recently we have now added two new undergraduate courses in computational physics: this course and 446. By simulating physical systems and observing their (simulated) behaviors, students can more efficiently grasp concepts that might be otherwise obscured by mathematical equations. By developing their computational skills, students are better prepared to assist in data acquisition and analysis tasks in a research setting. In addition, about half of our graduating majors choose employment over graduate study; they often report that prospective employers are seeking to hire employees with computational skills.

Acknowledgements#

The current version of this course is developed by Bryan Clark with updates (including the development of all the slides) by Lucas Wagner and Jaki Noronha-Hostler. An earlier version of this course was developed and run by George Gollin and this current version has non-trival overlapping units and problems. The classifying galaxy assignment closely follows a tutorial at the Galaxy Zoo. The fluid dynamics assignment was originally inspired to get you to develop lattice Boltzmann code similar to that from flowkit.com. The jupyter-ization of the course was done by Ryan Levy and Bryan Clark.